- The Fed SEP are inconsistent with low inflation, higher unemployment and yet no recession

- Our work agrees that inflation is falling. A trend that will accelerate in H2 and into 2024

- Yet the driver is weak demand, and our growth models suggest higher recessionary risk

- The big inconsistency in the SEP is employment, and we suspect the Fed knows it

While we tend to take central bank economic forecasts with a grain of salt and have spent most of our careers fading them, they are helpful as a fulcrum around which you can orientate policy expectations. In the case of the Fed, the starting point is their Summary of Economic Projections or SEP. Looking at the latest release, they tell us that the Fed continues to revise down growth this year, from 1.2% in September to 0.5% in December, with unemployment rising an additional 0.2% to 4.6% and essentially staying there through 2025. On the inflation side, headline PCE will drop to 3.1 and core to 3.5% from the current rates of 5.5% and 4.7%, respectively. At face value, they appear to vindicate the equity market’s assumption of a soft landing. But a year is a long time. Therefore, we thought it might be worth looking at where our work agrees or disagrees with the Fed’s assumptions.

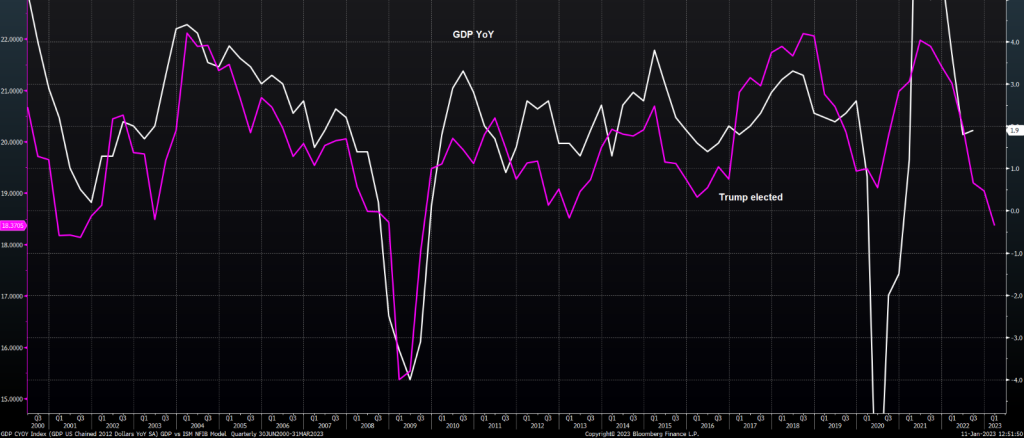

If we start with GDP, it is striking that the Fed isn’t forecasting a recession because, as discussed in our December Virtual Roadshow, our work suggests that tighter bank lending, together with inventory cycles in manufacturing and housing, are rapidly slowing US growth. For example, ISM Manufacturing New Orders are now below 47.2. The level we identified that in the last 50 years has always been followed by a recession unless the Fed punts the cycle by easing, which certainly isn’t in their forecasts!

This weakness is supported by our models, which suggest negative YoY GDP in Q2.

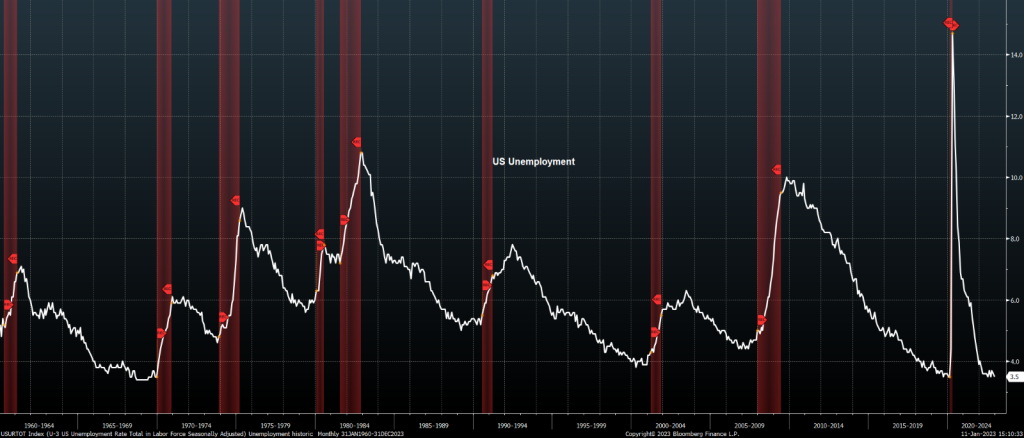

In fairness, the Fed’s forecast is for the whole of 2023. So perhaps, they think that after a glancing recessionary dip, growth will reaccelerate? Unfortunately, that brings us to the glaring inconsistency between their forecast of 0.5% GDP growth with 4.6% unemployment. Now, listening to Governor Waller’s speech on Friday, he certainly believes that, courtesy of structural changes in the labour market, this Goldilocks scenario is indeed possible. However, such an outcome doesn’t pass the historical smell test. That’s because in the last 60 years, following a peak in unemployment, it only requires a 0.6% increase to guarantee a recession, let alone the 1.1% they have in the SEP. If that’s not bad enough, the SEP assume unemployment will essentially track sideways at 4.6% for 3 years. However, we would remind you that once unemployment starts to rise, it doesn’t stop quickly, and the median increase in unemployment in a post-war recession is 3.3%, which would get us close to 7% (“Powell: Opportunistic Disinflation” 28th Nov).

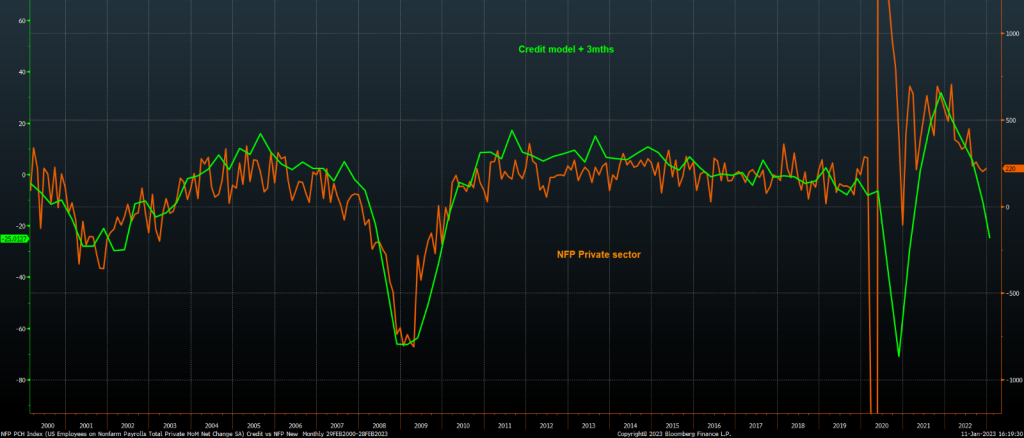

That brings us to our thoughts on employment. As discussed in the video, we love the Aggregate Weekly Payroll data because it’s a perfect snapshot of the broad labour market encapsulating hours worked, pay and total employment. The good news is that it is declining, which should help lower nominal GDP. The bad news is that it is still about 40% higher than the last decade’s average and miles above the level seen in the mild recession in 2001, which suggests that it’s premature for the Fed to back off and pivot.

If we delve a little deeper, our model suggests that the demand for labour is coming off the boil but that, for now, it remains too strong relative to the unemployment rate. This conclusion is confirmed by the latest ISM Manufacturing conference call in which the Chairman Tim Fiore commented that while the ratio of firms hiring vs reducing their labour force had dropped from 6:1 in the summer, it remained 2:1, hiring over!

The utter dearth of layoffs is glaringly apparent from the Initial Claims data. Yes, it’s true that claims are no longer collapsing at a precipitous rate as they did during the pandemic. However, the rate of change remains negative YoY. So, there’s nothing yet that supports the Fed’s forecast that unemployment is heading higher.

However, “yet” is the operative word because our work suggests that these dynamics will change rapidly once firms have filled those last positions they’ve struggled with since Covid. Hence, in Q2, we should be braced for negative NFP prints.

From that point, our work suggests a rapid increase in unemployment starting in the second half of the year to a level well beyond the Fed’s 4.6% number.

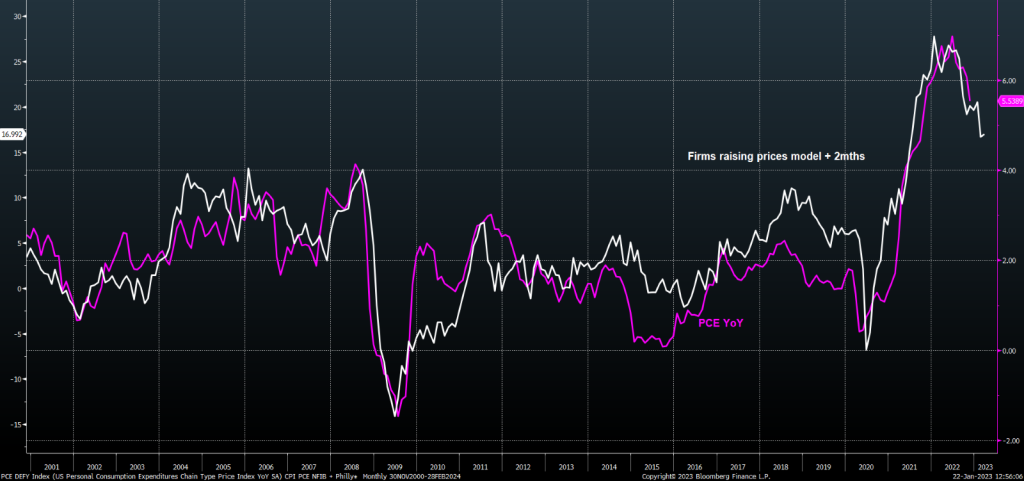

Finally, onto the topic of inflation. In September’s Q4 Roadmap, we discussed how after ramping up prices to protect margins during Covid, our corporate pricing models were starting to predict lower inflation. Fast forward a few months, and not only is that trend accelerating, but more significantly, the reason for the decline appears to be faltering customer demand.

“In an effort to drive sales and pass on cost savings, firms hiked their selling prices at the softest pace for just over two years” S&P US Manufacturing Survey

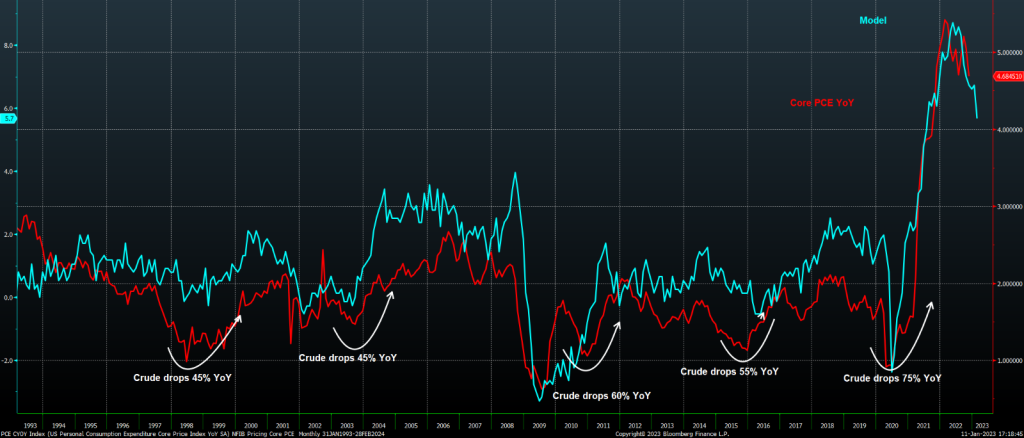

As a result, our models suggest that headline PCE will be close to 4.75% by the start of Q2. So, we are moving in the right direction. However, there is still a lot of work to achieve the Fed’s year-end 3.1% forecast.

As for core, that looks to be heading in the same way, with 4% in sight over the next few months, which also suggests the Fed’s target of 3.5% isn’t unrealistic.

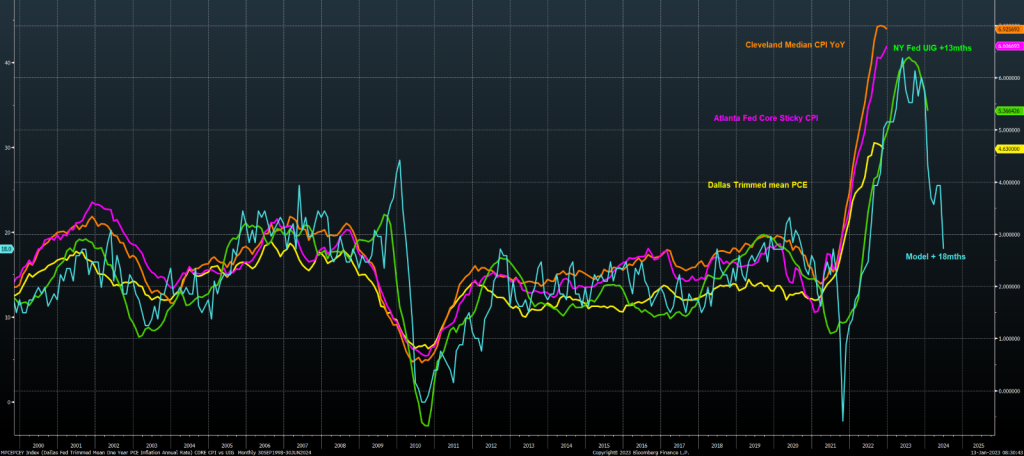

Furthermore, if we want to look 18 months into the future, even the Fed’s sticky or core price metrics look set to decline in H2 and quite markedly in 2024.

To sum up, our work suggests that inflation is moving in the Fed’s direction, and while their forecasts are ambitious, the direction of travel is clear. However, the only problem is that the forces behind weaker inflation are faltering demand and a looming recession, which in turn is undermining the ability of firms to pass on price increases. Hence, it would be a mistake to buy into the Fed’s inconsistent Goldilocks forecast, which has plummeting inflation with low but positive growth and a muted rise in unemployment. We suspect the Fed understand this only too well, and the contradictions are political expediency designed to avoid a direct conflict with DC. Instead, our work suggests that growth is set to turn decisively negative and if our forecasts of 6-7% unemployment are correct, then forget a soft landing.

Before we conclude, we should add the obligatory government health warning. The inputs underpinning the Fed forecasts and our models are highly dynamic. Therefore, while there’s very little chance that the trends we have highlighted will alter in the next few months, IF (a big one) the Fed fails to stick with their tightening programme in the second half of the year, the economy may be far more robust than expected. It is not our base case. But because of the profound market implications, we will examine the conditions necessary to create such an outcome next week.